Assignment Help and Writing Services in South Africa

Student Life Saviour has been providing assignment help and writing services to students in South Africa over a decade. Why are we highly acceptable among our students? It's all because of our experienced assignment helpers who are carefully selected by evaluating their subject specific knowledge and thoroughly analysed for their writing skills and abilities. So when you ask us for online assignment help, you will receive the best quality service within your specified deadline and budget.

You might think, "Why should I choose your assignment writing service?" You can consider us as we are the fastest assignment writing service provider in South Africa. With our academic writing services, you will definitely get more free time, less stress and efficiently meet your tight deadlines. You also have the option to select an assignment helper and order them saying "do my assignment for me" as they are available 24*7 at your services.

We are a professional assignment writing service company that you can actually afford. Our prices start from as low as ZAR150 per page, and we also provide discounts to help you save more while ensuring quality assistance. So experience quality writing services from our diversified team of assignment writers. Simply share your requirements through order form on our website, and a student friendly portal allows you to manage your assignment details. process payments and connect with expert.

If you have any queries, connect with our live chat representative to discuss your problems, and we will definitely help you.

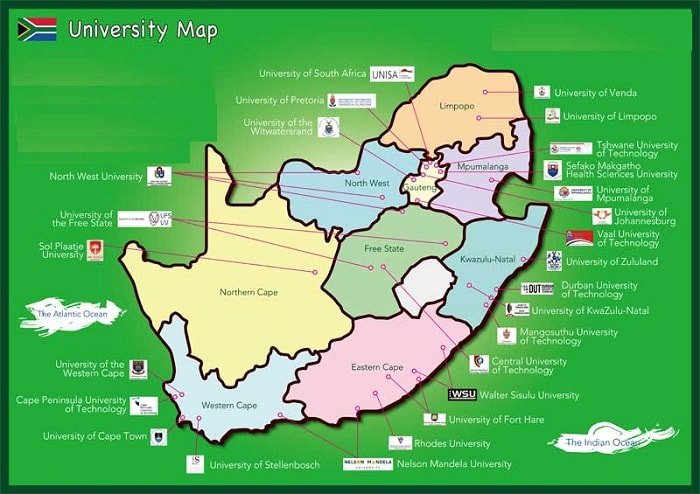

| Cape Town | Pretoria |

| Johannesburg | Durban |

| Bloemfontein | East London |

| Polokwane | Port Elizabeth |